Night was creeping in around the table where we were finishing a late dinner and a few beers, and I was beginning to drift in and out of our table's conversation. I hadn't really slept since leaving Olympia four days earlier, and the conversation was roaming wildly through topics as diverse as an apocryphal inner-city cult to Santa Muerte, and the enormous fanzine Siegfried Kaden had drawn in Sharpie all over a local gallery's walls. I lost track, looking out onto the street to a group of young men who were cutting open garbage bags in search of recyclables, under the patient gaze of a policeman. When I listened in again, I realized I was the topic of conversation, and my hosts were saying, "Yes, she should take him to Tepito." They sounded like they were daring one another to do something foolish, their eyes were a little wild. "No, it will be fine if he goes with someone who knows. It won't be dangerous, not really." A moment later I was holding a cellphone, and on the other end a young woman named Yutsil Cruz was saying "Please tell me a bit more about what you are doing, and tell me what you are hoping to find in Tepito." I babbled as best I could, certain that I wanted to see Tepito, whatever it was. The nervous energy in my hosts' voices when they said the name was enough of a reason for me. After a few moments of awkward explanations, Yutsil agreed to meet me at ten, the following morning. Glancing at the clock, I realized that I had less then eight hours to sleep and get ready. "Good," I thought, uneasily, "I won't have a chance to reconsider."

Tepito, I later learned, is the stuff of legend. It is said that Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec Emperor of Tenochtitlan, surrendered to Hernán Cortés in a place very near the center of Tepito, offering his own knife to the Spaniards in a request for an quick death, which Cortés eschewed in favor of torture and humiliation. From this point on Tepito's legend has grown.

The market has roots that go back, some say, "to the time of the gods," but during the seventies and eighties it attained enormous economic stature as a source for fayuca, illegally imported goods from the United States and abroad. During the decades when foreign imports were either heavily taxed or completely prohibited, Tepito emerged as the only place most people could afford to buy brand name clothing and electronics, as well as other highly desirable products from the other side of the US-Mexico border. The goods themselves arrived in large truckloads through border checkpoints that were adequately subsidized by smuggling organizations with strong bases on both sides of the border. There is a tale told that during this period the officials in Mexico City wanted to shut down the markets in Tepito, but its commercial allies in Texas were so heavily invested in the illegal merchandise there that they stepped in and prevented the government from enforcing its own trade laws.

Now, under NAFTA, there is no such thing as fayuca, and barely such thing as a trade barrier. Violating copyright law has become the new shortcut to accumulation, and the name for Tepito's bounty has been changed to pirata. Through the crowded pathways of Tepito's markets and stalls the wealth of the world's media production is offered up on stacks of hand-labelled compact discs, stored in photocopied sleeves. Complete collections of obscure anime series, British sitcoms, Scandanavian pornography, and Mexican norteñas lie side by side in neatly categorized piles. Booths sell counterfeit sneakers alongside genuine imports, and their vendors are happy to discuss the minuscule distinctions between the real and fake. In the next stall digital cameras and plasma-screen televisions are sold at cut-rate prices with no guarantee that they are indeed the brand they appear to be. A relatively recent development in Tepito is the sale of used clothing, imported from the saturated thrift-store market in the United States and sold by the pound in Tepito to distributors who resell the clothing in stores and market stalls through Latin America. Meanwhile, the fairy tales and rumours continue apace--that technicians in Tepito were the first to crack the piracy protection software on video games, or that they were the first to design the notorious chip that allows Playstions to run copied video games and play pirated films. As in the days of fayuca, Tepito still owns up to its mythical stature as an unacknowledged but unsinkable contestant in the battle between socio-economic heavyweights.

But Tepito's myth extends into dark places as well. The same corridors that offer a haven from the demands of governments and film studios also offer a place for illicit economies to distribute their product. It is rumoured that deep within the maze of Tepito there is a private firing range, where prospective clients can try out an assortment of weapons before making their final selection. Other booths offer prescription drugs and more "alternative" substances to those who know how to find them, and for every hundred youths shopping for music and clothing there is a bedraggled addict cruising the stalls in search of a stray purse or cellphone which might be traded for a sachet of heroin, only to reappear on the sale racks later as a discount item, a real steal. Some deserted eateries within the markets do not actually serve food, but offer more intimate company in private facilities above ground level. In accordance with the ruthless calculations of the open global market, it is certain that absolutely everything that can be counted, measured, copied, bought, sold, or stolen, there is a place for it in the stalls of Tepito.

Yutsil met me the following morning, and led me to an open doorway where a man was selling fresh fruit juices. We boarded a bus, and as we bounced along she explained that as an artist, she has always sought to create a social field within or around her work. When she was invited by a gallery within Tepito to do some work with them, she decided to set herself as a guide, extending an open invitation to artists and friends for a walk through Tepito, and a chance to meet some of its most prominent citizens.

The streets blurred outside my window, and I was concentrating on Yutsil and finishing my carrot juice. Then, quite suddenly, Yutsil said "Here we are!" and began weaving her way through the crowded bus and and out into the busy street. Blinking in the sun, I sheepishly asked "Is this really it?" After all of the hushed conversations and sidelong glances, stories of cults and freewheeling criminals, Tepito appeared to be pretty similar to the rest of Mexico City. Yutsil led me quite quickly along a wide, crumbling street filled with speeding buses and taxis, lined on both sides with awnings and racks of cheap merchandise. The most apparent danger was from taxis shouldering past within inches of my feet. Still, I was nervous, and I slid my backpack underneath my shoulder in some vain effort to protect it from being grabbed by an opportunist. Perhaps I was being needlessly cautious--I later heard a story that Tepiteño merchants are known for actively policing their own stalls, whenever pickpockets begin to have an impact on the pace of business. When they find someone stealing, they chase him down, shave his head, take his shoes, and then send him along through crowded streets to find his destiny.

Yutsil turned sharply, leading me into a maze of shops and bodies, then around a corner into a quiet courtyard. There was a sign on wall that read "Association of Established, Partially Established, and Fully Mobilized Businesses from the Barrio of Tepito." I'm translating pretty loosely, here, especially with the word ambulante, which is specifically used to describe the practice of vending wholesale and pirated goods from a portable stand set up on the side of the road. If one were feeling poetic, ambulante might be translated as "trafficker in the ephemeral".

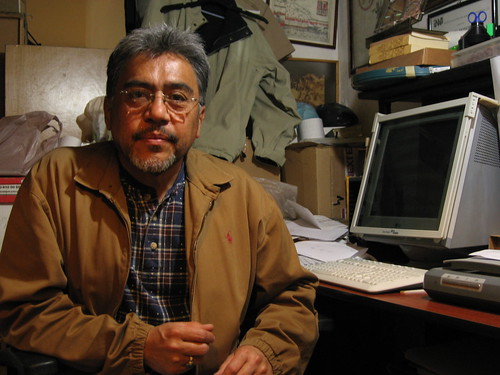

The office that opened onto the courtyard contained five or six neatly spaced desks, behind each of which was seated an older man, busy with papers and letters. In the middle of the room, a group of uniformed children were eating lunch and listening to a story before returning to their school for the afternoon. We were here to meet Alfonso Hernandez, the founder of the Centro de Estudios Tepiteños and self-assigned historian for the neighborhood. His office is filled with books, in stacks, including several unique editions of a few of Benjamin's lesser known works, photocopied in their entirety and bound with wire. A special note on the cover of these books reads: "Limited Edition, Printer's Guild of Tepito". Alfonso works as a guide and liaison for the various anthropologists and UN fieldworkers who prowl through Tepito's markets, and he has been invited to discuss his work at conferences in London, Warsaw, Amsterdam, Bogotá, and elsewhere. "They all want to know how we do it," he told me, "How we can exist without becoming part of a larger governmental structure."

In conceptual terms, Tepito has persisted for decades as an working space wherein Mexico's governmental authority has almost no direct control over the lives of Tepito's citizens. The state's principal modes of expression, from the administrative to the carceral, are either ignored or denied entry into the complexity of Tepito's economy, warded off by the dynamism and efficiency of its rhizomatic self-organization. The expansive reach of its reputation for danger and lawlessness is a good signal of Tepito's success as an alternative to the societal structures beyond its outer edges--that which is incompatible with the fabric of established institutions and orders appears within those orders as unapproachable, inadvisable.

The men seated in neatly spaced desks outside of Alfonso's office, I can now presume, were a few Tepito's sixty-two prominent lideres, who together form something like a council of representatives for the merchants and residents of Tepito. Their posts are awarded according to their experience, success, and prominence, and the degree to which they defer to the best interests of their constituency is not clearly defined. There are many in Mexico who suggest that this system of government is more closely based on a Sicilian model than an Athenian one, but they are not acknowledging the genuine complexity of the situation.

Between 1972 and 1982, in turn of militaristic city planning that united twelve governmental agencies, the city's "Plan Tepito" was unveiled. In essence, the plan eliminating all existing structures and rezoned the area for the light commercial and low-density apartment residences more in tune with the modernizing image then being encouraged by Mexico's dialog with the World Bank. The residents of Tepito, recognizing the threat levelled at them, petitioned alternative plans from student architects and international artists. These invitations resulted in a much elevated visibility of the community as it stood, winning design prizes and inspiring sympathetic civic projects as far away as Lyon, and succeeded in putting a stop to the city's plans.

Today, along the main street of Tepito's markets, a long stretch of elevated shops has been built over the ground level, doubling this area's capacity. As we walked past, Yutsil pointed these structures out, saying "They built this, the merchants did, with their own money, and their own plans. They never got permission from anyone. It shouldn't be here, but it is." When I asked how the construction of this structure was related to the sixty-two lideres, Yutsil confirmed my suspicion that they would have been instrumental in the planning and execution of this project. When I pushed for details, she told me she knew almost a little as I did. The structure of Tepito's preferred administration, it seems, is a bit more nebulous than its dominant counterparts.

I asked Alfonso about child care, hoping to find out about a specific example of community organization. Alfonso shook his head, saying, "Look, here all networks are informal. Our past experiences have taught us to atomize our organizations, in order to prevent any sort of political control. Having an identifiable hierarchy would simply attract the attention of the police." He hadn't really answered my question about childcare. I remembered the table full of uniformed children eating lunch and listening to a story, and behind them the row of leaders planted in their desks.

"Here, you won't encounter illiteracy. In Tepito we are in contact with the greatest technologies of the entire world. But in the schools they are teaching unnecessary things. They are preparing the children for a kind of life they will never have." When Alfonso said this to me, I was immediately struck by the conflict between the two models of citizenship available to a child in a neighborhood such as this. One, the white-collar, mortgage-paying worker who fills their apartment with laptops, hybrid cars, designer jeans. The other, a technology savvy, freewheeling entrepreneur thriving within the blinding pace of business in a world of piracy, cloning, and informal rent agreements in neighborhoods on the edge of legality. The prior struck me a fantasy justification for the advance of neoliberalism, the latter as its unmistakable reality. Illegal, improvised, opaque, according to unwritten agreements and unmistakable necessity, the citizens of Tepito have crafted a new form of government for themselves. The challenge they face is to retain their hard-won position, in the face of transnational accords and corporate development schemes that, by dearth of positive effects, appear to simply be the most successful form of organized crime in North America.

"Tepito's identity is found in a balance between its charisma and its stigma," Alfonso said. "It has a history of being the barrio that fights for its place, that defends itself in a city that would like it to disappear. We have learned from the example of cities like Los Angeles, where the process of urban renewal shuffles the poor from one place to another according to the whims of real estate speculators. But in Tepito we have never raised political banners. We have defended ourselves with artistic and cultural expressions, which exist outside of the criteria used by our government. Our charisma is in our culture of poverty, and it overcomes the stigma of our marginality, organized crime, and addiction. To one another we say 'A barrio without shadows instills no respect, and so we spread rumors, we make our shadows darker.'"