In an attempt to counter this, the Fundacion Centro Historico was established to recuperate the center as a living space for families and small businesses. Backed in part by the enormous and controversial power of Mexico's richest man, Carlos Slim, the foundation embarked on a multi-faceted project to recover the historical center's community. Initially conducting psychological studies and establishing child-care centers, the foundation later decided to divide the city center into thematic corridors, in order to specialize its involvement in specific neighborhoods. It developed a technological corridor, an entertainment area, a small business area, and it selected a set of intersecting alleyways as the site for its "cultural corridor." Seeking to foster an artistic community, the city cooperated with the foundation in offering affordable lofts to young artists, renting spaces to galleries, establishing a small museum, and linking all of this to a nearby university. Also, the planners created a youth hostel for visiting art students called La Señorial, which is running and available to all.

Casa Vecina was conceptualized as a space to support community-focused art programs, and as a project to strengthen the relationship between long-term residents and newer arrivals. It aimed itself at a different audience other than existing consumers of conemporary art, seeking to draw in the grocers, restauranteurs, tailors and other full-time residents of te historic center. After a year of remodelling and planning, the Casa Vecina began its projects, opening its spaces to local and foreign artists, and to the community around its doors.

I spoke with Iván Edeza, the Casa's artistic director, about some of the strategies the center is using to make their programs available and accessible to the people of the surrounding community.

Workshops

In the year since its opening, the Casa Vecina has been offering a variety of art classes to the children of the community. They decided that rather staying within traditional genres of art teaching, they would offer thematic classes like puppetry, pottery, and theater. "We gave workshops without specifying what kind of 'art' we were doing," Iván said. This summer, they are planning to offer a course in making movies to neighborhood adolescents, and then to exhibit their films in a community film festival held at Casa Vecina and nearby locations.

Initially, these classes were offered to the community free of charge, but the center began to sense that parents were sending their children to workshops simply so they would be out of the house, rather than out a genuine enthusiasm for making art. Children were arriving without focus, goofing off, and making it difficult for instructors to ruin their workshops. "Adding a small fee," Iván told me, "made all the difference," and since this time they've had a drop in attendance but a great deal of improvement in the interest level of the students who attend.

"The important question to ask," Iván said, "Is whether art is really for everyone. In truth, I don't think it is for everyone. But I don't think this distinction is made according to one's affluence, but according to the level of one's interest. I think my job is to make a new opportunity available, and to put it out there for people to enjoy, if they wish. Museums are so cold, they require so many codes just to get through the front door. We are making a few minor changes, to try to make art more accessible."

El Callejon

Out in front of the Casa Vecina is a patch of freshly lain tiles and paving stones, embellished on one side by some iron stumps to stop cars from passing through. When the Casa Vecina was first opened, this alleyway was a throughfare for taxis and speeding motos, lined on both sides with trash. One of the center's first projexcts was to collec siognatures and arrange funding to stop traffic through the tiny street. It led the community in a series of work parties to clean the street, tear up the old asphalt, and intall the new pavement. Their hope was to make it a place where children could play, and on most afternoons there is are at least a pair of kids kicking a ball back and forth. On the afternoon that I was visiting, Casa Vecina's director Antonio Calera Grobet was standing outside, locked in conversation with several other members of te center about how and where to install a bicycle rack. In a city reknowned for its pollution and pettty street crime, the amount of cycle communitng that occurs is negligible, but their plan is wonderful in its optimism and assertiveness.

"Un Espacio Convivencial"

Recently, the center has begun projects dedicated to creating a shared sense of space in the street, and in collective activities. They have begun setting up community gatherings around the neighborhood, and leading thematic walks through their streets. "We're thinking about things like assembling a group of cyclists for a ride around the community to visit cycle repair shops, in order to meet with cycle mechanics and talk with them. Later, we could hold an exhibition of interesting bicycles in the center, and have a screening of Vittorio De Sica's film The Bicycle Thief!"

A related strategy has been to arrange neighborhood outings to other parts of the city to see exhibitions that ordinarily would escape local notice. The center is organizing just such a visit to see the Gabriel Orozco retrospective at the Palace of Fine Arts, about ten blocks away, followed by a group stroll and a visit to the comissioned installation Orozco made in a nearby library.

"Now, more than being a place people come to for art lessons, we are hoping to become a place people can move outwards from, into other parts of the center. Our goal is to assist people in recognizing the vibrancy of their own community, seeing their own lives with interest and excitement, and enjoying the vast amount of heritage we have aound us here. We want people here to appreciate their own houses, because in a community as old as this one it is often said that the houses are ugly, they are falling down. When you watch the telenovelas you see modern houses, suburbs, and we want to redirect everyone's attentions to the beauty we have around us."

La Cascarita

Casa Vecina's newest staff member is Victor Ibarra, who has lived within the center for his entire thirty-nine years, working for the last ten as the manager of a bar called La Cosmopolitana. He will be working with the center to further improve the relationship between the budding art community and its neighbors, taking advantage of his vast network of family, friends, and aquaintances in the area. When I was in Mexico City, Victor hadn't yet begun his new job, and over a drink at La Cosmopolitana he told me how he'd made the transition from bar manager to cultural liason.

"We were all pretty aware of Casa Vecina, because it took a year to restore the building, and we'd pass by. One day a friend of mine came into La Cosmopolitana and said 'Hey, what's up wit that new place around the corner?' They'd built a bar into the bottom floor, called La Bota. I liked to go and get a drink there, because it was a quiet place.

"One day I noticed a little poster advertising art classes for kids upstairs, and when I got home I told my wife about the classes. I have a daughter who is ten and a son who is six. We signed them up for a drawing class and some acting lessons. So, a few times a week, I'd bring them over to the Casa Vecina, and while they did their classes I'd have a beer at the bar. I got along right away with Antonio, who owns the bar [and is also the director of Casa Vecina]. It was great, there was some art for the kids and some downtime for the grown-ups.!

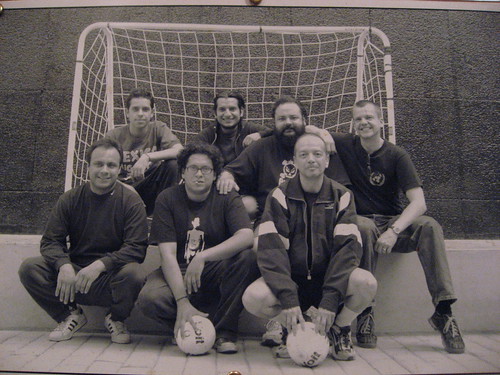

"Well, last summer the Fundacion Centro Historico was encouraging small community events, for families, to take place in different parts of the neighborhood. Antonio told me about it and I decided to really get involved. I invited my brother's family, and we all started to make some plans. We thought it would be a great thing if all of us played a few games of football, in the street. When we play out in the street we call it a cascarita, when there's no referee, no real firm rules, and someone's always shouting to everyone else 'It was out! It was in!'

"We had six teams: two for young kids; two for chavos, fourteen to sixteen; and then on one side we had a bunch of us from La Cosmopolitano against the guys from La Bota. You know, it was more to play for the joy of the game than to win or lose, especially for us older guys."

"La Cosmopolitana"

La Bota

"It turned out that a whole bunch of my family showed up to watch the games. My mom and dad were there, and the families from everyone at La Bota came down as well. So we played football all morning, and then we all ate together. We brought some steaks and stuff, and Antonio brought a case of beer out from La Bota. It was the day of the World Cup Final, so we all sat down together and watched Italy beat France.

"That's how I got to be friends with Antonio and Casa Vecina. Later on, I was telling Antonio how tired I was, how my ten years in the bar were catching up with me, and he said 'Why don't you come work with me? You know everyone around here, you've lived here your whole life, we need your help.' I thought about it, and I thought, 'Sure, I'll be coming from outside, with my own perspective, and without a really fixed idea about what "art" really is.' I see this as my first chance to really work for my community. It's tough, because so many people say 'Oh, I don't have time,' or they want to go to the movies, or the domina hall, or the cantina. Yeah, it will be really difficult, but I'm thinking it will be really great.

"We're even using La Cosmopolitana for art shows. We just had one here, called Acerca de la Lucha, which was a set of paintings of boxers. You know, lots of people who own shops around here, they don't have time to go home for lunch, so they come in here. They saw the show, and now a lot of them are asking, 'Where are those paintings?' We're thinking about putting up a group show. We're even talking about showing documentaries or film projects on the television in here, instead of music videos, but we'll need a lot of them so it doesn't get repetitive. So, even though I'm moving over to Casa Vecina, there's a really great relationship between these two places, and we can keep working together."

Fireworks

I'd only intended to spend the afternoon at Casa Vecina, but after several long conversations I found myself still fixed at a table in La Bota, hoping to find someone to else to talk with, more perpsectives. I looked out at the alley Casa Vecina had restored a few months earlier. It extended a few yards past the front door of the center, then sharply changed into a hard packed dirt street that may, at one time, have been paved. Past that point the alley darkened, and I wondered when, if ever, the warmth within La Bota would expand out into the far reaches of the community, now shrouded in darkness. The security guard employed to keep watch over the block, not an uncommon sight in Mexico, strolled past the open walls near my table.

Once, in conversation, Iván interrupted me to point out a group of street kids who had pulled open the garbage can across the alleyway, and were hunting methodically through soda bottles and fruit rinds for something of value. As night fell around the bar, a pair of teenagers paced nervously back and forth in the alleyway. They were carrying a bag of fireworks, and occasionally would light a really loud one somewhere out of sight. I noticed that as I spoke with Iván and Antonio, their eyes would drift over my shoulder to the alleyway outside, where the teens leaned against one of the iron stumps the center had installed. Then, just when all of us were deep in conversation, a huge bang sent me out of my seat, and it was clear that the firecrackers were beginning to be a little too close to La Bota to be an accident. When I looked outside, I saw Antonio lecturing the two culprits, gesturing with one hand. When he came back I went to stand at the window with him, where we looked out to where the boys were still leaning against the stump, looking sour and insulted.

Antonio's mind seemed to be racing, working to produce a solution to this dilemma that worked for all parties. He looked at me, as if to ask what I would have to say about this incident. He said "You know, we're not the bad guys, here. We made this for them. We are doing this, and we aren't going anywhere. They have to respect us."